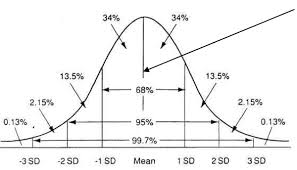

Transgressive Fiction is "a genre of literature that focuses on characters that feel confined by the norms and expectations of society and who break free of those confines in unusual or illicit ways. Because they are rebelling against the basic norms of society, protagonists of Transgressive Fiction may seem mentally ill, anti-social or nihilistic." (Wikipedia) From this definition, we understand that author's such as Burroughs, Shelby, Genet, Miller, Ginsberg belong to the genre, and inculcated as we all are from birth, it is understandable that what we easily recognize as "transgressive" is a kind of game of whack-a-mole, wherein our hero rebels poke their rebellious heads up only to, sooner or later, have them whacked back down by society. It's a game the house always wins because it sets the parameters. But what if we step beyond easy recognition? What might we find there to inform us about literature and about life? Last month I reviewed Never Anyone But You (discovered on the terrific site transgressivefiction) and concluded, "It is an interesting choice to include in the "transgressive fiction" tent. It contains little of the usual canon; this is not a story of rebellion via drugs, criminality, nihilism or self-destructive decadence. Claude and Marcel defy oppressive norms by creating a happy and long life together, by not internalizing the normative paradigm but designing and defining their own." I think we take too narrow a view of transgression when we see only "drugs, sexual activity, violence, incest, pedophilia, and crime," to quote goodreads. Not that there's anything wrong with those things in fiction of course, but what I mean is this: if the bloated center of a bell curve represents society ("everywhere in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members," as Emerson tells us), then transgression extends in many directions. It is these heretofore unrecognized directions, and the fiction that explores them, that is the subject of this month's Censorable Ideas. From The Atlantic Monthly: "Transgressional fiction shares similarities with splatterpunk, noir and erotic fiction in its willingness to portray forbidden behaviors and shock readers. But it differs in that protagonists often pursue means to better themselves and their surroundings—albeit unusual and extreme ones. Much transgressional fiction deals with searches for self-identity, inner peace and/or personal freedom. Unbound by usual restrictions of taste and literary convention, its proponents claim that transgressional fiction is capable of pungent social commentary." This description begins to take us somewhere interesting. Can fiction be transgressive in a positive direction? I offer in the affirmative the following examples: Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, The Baron in the Trees by Italo Calvino, The Benaroya Chronicles trilogy by Jody Scott, Headhunters from Outer Space by Bret McCormick Never Anyone But You by Rupert Thomson The characters in these novels subvert & disobey the imperatives of their society, not in the easily recognized transgressional fiction modality, but critically, to my point here, for the same reasons. These protagonists SEE the normative paradigm, with all the banal hypocrisies and suppressions thereof, but reject it by flourishing in a paradigm of their own making. "Resistance is futile," warn the species-gobbling Borg in Star Trek, and we've all heard the truism, "what you resist, persists," so perhaps they make a good point. Perhaps it's a problem with our understanding of transgression as synonymous with rebellion. When we look to the dictionary definition of rebellion ("An act of violent or open resistance to an established government or ruler. The action or process of resisting authority, control, or convention"), we begin to see how the game of whack-a-mole rebellion cedes society victory from the start. Maybe what's needed is a broader concept of transgression, something that doesn't accede that society's paradigm is the benchmark, against which we can only rebel. Like Claude and Marcel in Never, Scott's characters Benaroya and Sterling O'Blivion, Calvino's protagonist in Baron, McCormick's Headhunters and Don Quixote are examples of "transgressors" who defy societal norms by the more evolutionary and difficult task of not internalizing the dominant paradigm. Easier said than done (but not impossible) in life, of course, but these are fictional heroes who transcend the "games condition" of poking their heads up for society to take a whack at.

As imagined by these and other authors, characters "who feel confined by the norms and expectations of society and who break free of those confines" in positive directions can and do make critical points about society, may "portray forbidden behaviors and shock readers," but most importantly these protagonists "pursue means to better themselves and their surroundings." They give us permission and inspiration to imagine better, bigger, richer, freer than the world would have us believe is possible. And what is more transgressive than that? -Mary Whealen

0 Comments

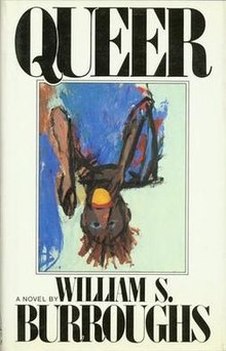

Once upon a time in a mall in Orange County CA with my paternal aunt and her husband, as we were exiting past Barnes & Noble Jody and I noticed a display of William S. Burroughs' newly published novel, Queer, which naturally we rushed over to look at. Dozens of copies, stacked high, the word queer repeating over and over in large, bold type. My Catholic aunt (rabid fan of Elvis, who once gigglingly exclaimed, "He can park his shoes under my bed anytime") and her husband (soon-to-be transplants to Colorado Springs CO, birthplace of the 1992 anti-gay hate bill Amendment Two, of which they were staunch supporters- not that we knew that then of course) were shocked. It was scandalous that a publisher and a mainstream bookstore in a mall in conservative Orange County, and Jody and I by our attention, together with some degenerate writer were forcing the "gay agenda" upon their delicate heteronormative sensibilities. Or so I assume it seemed to them. Which anecdote I share with you because it's sadly absurd, but also apropos as introduction to this month's Censorable Ideas post about William S. Burroughs, Jody's minor connection to him, and some musings on queer and other "outsider" writers who influenced Jody and WSB.  Michael Stevens is a Burroughs scholar who recently contacted me about WSB's connection to Jody (he wrote a nice comment about I, Vampire when it first came out) for future editions of his book. The Road to Interzone: reading William S. Burroughs reading is "an index to the books known to have been read, blurbed, or cut up by the author of Naked Lunch," including any known commentary on that work or writer, and it is surprisingly revelatory as a portrait. While this may not be the sort of titillating page-turner you read cover to cover, it is a fascinating treasure trove of insights, influences and previously unknown writers you'll want to dip into again and again with your laptop open to google and your favorite bookseller. Highly recommend. Two writers that were unknown to me are Jack Black and the POET LOUISE BOGAN.  "Jack Black’s You Can’t Win was probably the longest lasting literary influence on Burroughs’ writing . From his first novel to his final memoirs he was making references to its characters and philosophy. He incorporated the hobo jungles, the criminal code, cat burglars, safe crackers, robbers and rodriders into his mythology and virtual worlds. WSB’s appreciation of the nobility of the criminal and the underground lifestyle found its inception here. Many readers are not even aware that the Johnson family and Salt Chunk Mary are not Burroughs’ creations, but key players in Black’s work. Burroughs first read the book when he was fifteen and it had a profound effect, not only on his literary life but his personal life as well. His reading of You Can’t Win was his earliest exposure to the criminal lifestyle that he attempted to recreate in his life and his fiction from that moment on." (Interzone) It's worthwhile asking here why artists are attracted to the forbidden and the outlaw. The great American sage Ralph Waldo Emerson explains it this way: "Society is a joint-stock company which the members agree for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion. It loves not realities and creators, but names and customs." To violate these customs is to invite society's punishment, be it ostracism in the schoolyard, mass incarceration of black folk, or coercive economic duress.... What artists, writers, and outlaws have in common is an instinctual rage against this. ("Society represented law and order, discipline, punishment. Society was a machine geared to grind me to pieces." -You Can't Win) In the case of the criminal, this manifest as self-destructive sociopathy; in the case of Burroughs, Jody Scott, et al it gives us great art and literature, music and philosophy- all that counterbalances the oppressive side of society and makes of it (sometimes) a civilization. Another who influenced both Jody and WSB- and celebrated the outcast and criminal- was the french novelist Jean Genet. Jody considered him a tremendous stylist and her transgressive gay novel of the 70's, Kiss the Whip, was greatly influenced by him. "Burroughs consistently listed Genet among his favorite writers and on several occasions said that Genet and Samuel Beckett were his favorite authors. 'Every man, no matter what his sexual tastes- likes the characters in Genet'" (Interzone) For your pleasure and scholarly edification, here are excerpts from Genet, Burroughs and Scott:  You should have listened to me lover and abandoned this journal but now it's too late, much too late. To pry into St. Michael's life is to invite that most terrible curse, the Deuce of Vapors. Do you know how serious this is? Remember one thing. Whatever happens, dear reader, I love you. Watch closely as I come to the forefront of the canvas and look you straight in the eye--lock eyes!, Goddamn you, you evasive little bastard, and listen: "love" is much too timid a word; I adore you, my stone angel with the greedy greedy mouth. We deserve each other! For despite my flaws and crimes I am the One you've waited for, such a long time, such an empty, barren, windswept, crying-in-the dark long time, my darling. -Jody Scott, Kiss the Whip  Before Armand had granted me the esteem of which I have already spoken, I probably would not have betrayed him. The mere idea would have horrified me. So long as he had not given me his confidence, betraying him had no meaning: it meant simply obeying the elementary rule which governed my life. But now I loved him. I recognized his omnipotence. And though he might not love me, he contained me within him. His moral authority was so absolute, so generous, that it made intellectual rebellion within his bosom impossible. The only way I could prove my independence was by acting on the emotional level. The idea of betraying Armand set me aglow. I feared and loved him too much not to want to deceive and betray and rob him. I sensed the anxious pleasure that goes with sacrilege.. ― Jean Genet, Thief's Journal  A curse. Been in our family for generations. The Lees have always been perverts. I shall never forget the unspeakable horror that froze the lymph in my glands--the lymph glands that is, of course--when the baneful word seared my reeling brain: I was a homosexual. I thought of the painted, simpering female impersonators I'd seen in a Baltimore nightclub. Could it be possible I was one of those subhuman things? I walked the streets in a daze like a man with a light concussion--just a minute, Doctor Kildare, this isn't your script. I might well have destroyed myself, ending an existence which seemed to offer nothing but grotesque misery and humiliation. Nobler, I thought, to die a man than live on, a sex monster. It was a wise old queen--Bobo, we called her--who taught me that I had a duty to live and bear my burden proudly for all to see, to conquer prejudice and ignorance and hate with knowledge and sincerity and love. ―William S. Burroughs, Queer  There are many authors I could include here, and I may well return to this fertile subject in future Censorable Ideas, but for now I will conclude with the other new-to-me writer from Interzone (though not a direct influence on either Jody or WSB), the poet Louise Bogan. a brilliant minor poet of the ‘reactionary generation.’ Yes, Bogan is indeed a “minor” poet, but that does not mean she isn't worth reading. As the Poetry Foundation website puts it, “her poetry is modern and emotive without being sentimental, and her language is immediate and contemporary.” A woman born in 1897 insisting upon her right to live her life her way (something hardly acceptable for women today, revolutionary then) definitely qualifies as a societal “outlier.” In a letter to Theodore Roethke she writes, “I, too, have been imprisoned by a family, who held out the bait of a nice hot cup of tea and a nice clean bed. . . the only way to get away is to get away: pack up and go. Anywhere. I had a child, from the age of 20, remember that, to hold me back, but I got up and went just the same, and I was, God help us, a woman.” "Burroughs may have been familiar with her work as a youth, but didn’t make reference to this poem until The Western Lands,” writes Stevens in Interzone. The poem that caught his eye was SEVERAL VOICES OUT OF A CLOUD and it seems a fitting note to end on: Come, drunks and drug takers; come, perverts unnerved! Receive the laurel, given, though late, on merit, to who and wherever deserved. Parochial punks, trimmers, nice people, joiners true-blue, Get the hell out of the way of the laurel. It is Deathless And it isn’t for you. * * * -Mary Whealen |

Get blog via email or reader:Categories

All

Archives

June 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed