|

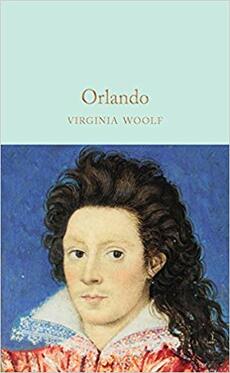

When I was growing up in California, going to Disneyland was a part of life. Every several years my mom, sister and I would pack up the station wagon, head south on the 101, then with high excitement, buy our coupon books at the gate. During one visit my mother and sister wanted to go to the Enchanted Tiki Room but I wanted to visit the Swiss Family Treehouse, so we split up. My attraction sucked. Mom and sis praised the Tiki Room highly and I wished I'd gone to it instead. It was many years before I was at Disneyland again and finally got to go to the Tiki Room; I expected an animatronic paradise of lush jungle and exotic singing birds. Imagine my disappointment when instead it consisted of bleacher seats in the round and a pantomime of a corny nightclub act with birds. Sometimes reading a book is like the Tiki Room. This month's Censorable Ideas is about 2 such novels, Orlando by Virginia Woolf Riding the Centipede by John Claude Smith.  Orlando is a novel praised in breathless whispers as "groundbreaking," and it's true, the notion of fluid gender roles would've been something new and shocking for its day, and the fact that the protagonist changes sex in the novel might be taken as prima facie evidence of challenging social gender-role orthodoxy, but Orlando the titular character, as first a boy and then a man and then a woman, largely conforms to the social expectations of each of these identities, and so I think Orlando the novel gets more credit than it earns in this regard. Maybe, like with the Tiki Room, I'd read so much praise of it before actually reading the novel, that it became more in my imagination than it could possibly be, and disappointment was inevitable, but my overarching impression was this is a novel that marries the worst instincts of chick-lit (albeit at a far superior level of writing) with the effetest of the effeteness of upper class idleness. "Oh I'd love to be a writer!" Orlando cries for 400 freaking years, like a teenager writing in her diary, and, despite his/her four centuries of experiences, learns nothing, grows not a wit as a character, remains the same overly-sensitive, narcissistic juvenile throughout. Perhaps it was Woolf's intention to show that no amount of life experience can overcome the debilitating effects of too much wealth combined with too little purpose, though I doubt it, but that is certainly my take-away theme. Now as a very long love letter to Vita Sackville-West, which Orlando is widely considered to be, it is astonishing; there is much humor to be enjoyed, and Woolf is undoubtedly a master of her craft- her prim, precious, introverted prose is perfectly matched to the subject matter, but I find the character of Orlando to be too useless a waste of space to be able to like the novel.  Riding the Centipede presents itself as transgressive fiction, "a genre of literature which focuses on characters who feel confined by the norms and expectations of society and who break free of those confines in unusual or illicit ways," but what it ultimately delivers is something quite different. "Riding the Centipede," we are told by Marlon, longtime junkie and denizen of the underworld, is the ultimate drug-fueled experience. Created by a mythologized William S. Burroughs and offered just once a year exclusively to one recipient, Marlon has been chosen. Now all he has to do is survive. Centipede is the story of his journey, and his sister's parallel quest to find and rescue him, assisted by a world-weary P.I. There is of course also an evil "Ubermensch" antagonist, and an assortment of unsavory characters whose debased wishes Marlon must fulfill in order to receive the drug to take him to the next level of his ride. The thing about transgressive fiction that makes it interesting and valuable, is that, at its best, it leads us to other avenues of contemplating reality, to different ways of thinking or experiencing that transgress society's paradigm in order to gain a bigger, freer point of view. Not so with Riding the Centipede. We get all the trappings of TF, but none of the payoff. There is, ultimately, no ultimate experience; we never get to take that ride and the characters who seek it... well it ends badly for them. The characters for whom it does not end badly find happiness in a conventional life that conforms to society's expectations. Smith has undoubted talent, but this novel reminds me of the pulp lesbian and gay fiction of the 1950's and 60's: it was OK for characters to indulge their "deviance" so long as by novel's end they converted, died or were punished. The characters in Centipede likewise indulge their deviance but in the end, convention's imperatives are upheld. I felt that in the back matter of this ebook, there could've appropriately been an animated GIF of Nancy Reagan holding a sign proclaiming, "Just Say No." Which is what I say about Riding the Centipede. -Mary Whealen read more reviews

0 Comments

This month's titles come courtesy of transgressivefiction.info, a great place to discover new and interesting authors. THE EXIT MAN by Greg Levin |

Get blog via email or reader:Categories

All

Archives

June 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed